"As a form, the origins of the grotesque aesthetic lie in the visual arts."___*

"The grotesque is not an expression of norms, but rather what results from the transgression of them (Dieter Petzold "Grotesque" The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children's Literature.) In recognition of the grotesque as “the slipperiest of aesthetic qualities” (Geoffrey Harpham “The Grotesque: First Principles” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism.) the flurry of nineteenth century writers addressing the grotesque did so by exploring its aesthetic, social and philosophical significance. (“An Introduction to the Grotesque: Theoretical and Theological Considerations” The Grotesque in Art and Literature: Theological Reflections Ed. Adams, James Luther and Wilson Yates.)

The word itself is rooted in the sixteenth century Italian excavation of ancient palaces, tombs and villas such as Nero’s Domus Aurea in Rome, and the discovery of a fantastical decorative style in the underground chambers called grotte. (Gordon Campbell, ed. “Grotesque" The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts.) Within the century the term had spread to France and England, where its definitive scope broadened from decorative motifs to encompass literature and even people."___**

"Even in its antique origin, the grotesque carried something “ominous and sinister" a world totally different from the familiar one (Kayser, Wolfgang. The Grotesque In Art and Literature. p.21). Wolfgang Kayser, in his history of the tradition quotes from Vitruvius’s On Architecture (circa 23 BC) whose commentary reveals the shock the original form presented when first employed:

"Our contemporary artists decorate the walls with monstrous forms rather than reproducing clear images of the familiar world. […] they paint fluted stems with oddly shaped leaves and volutes […] dainty flowers unrolling out of roots and topped, without rhyme or reason, by figurines. The little stems finally, support half-figures crowned by human or animal heads. Such things, however, never existed, do not now exist, and shall never come into being.""___*

"Despite some notable, but isolated, attempts in the nineteenth century to define the nature of the grotesque, it was not until the appearance in 1957 of the book by the late German critic Wolfgang Kayser, The Grotesque in Art and Literature, that the grotesque became the object of considerable aesthetic analysis and critical evaluation. Where previous ages had seen in it merely the principle of disharmony run wild, or relegated it to the cruder species of the comic, the present tendency—one which must be welcomed as a considerable step forward—is to view the grotesque as a fundamentally ambivalent thing, as a violent clash of opposites, and hence, in some of its forms at least, as an appropriate expression of the problematical nature of existence. It is no accident that the grotesque mode in art and literature tends to be prevalent in societies and eras marked by strife, radical change or disorientation. Although one runs the risk of succumbing to clichés when one regards the past forty or fifty years as just such an era convulsed by momentous social and intellectual changes, it can nevertheless be fairly said that this is an important contributing factor in the present artistic situation, where the grotesque is very much in evidence. Even a quick random sampling of what is being currently produced—with such names as Harold Pinter and Joe Orton in England, J. P. Donleavy and John Barth in the U.S.A., Samuel Beckett and Eugene Ionesco in France, Günter Grass in Germany and Friedrich Dürrenmatt in Switzerland—will attest to the extent to which the grotesque has become a favoured mode in world literature. This is not to speak of the other arts, where a similar situation prevails."___***

___*"Everything Off Balance" A Master's Thesis in American Studies at the University of Virginia, Site Author: Caleb P. Dulis

___**grotesque Inga Kim Diederich: Art History and Visual Arts, The University of Chicago, Theories of Media.

___***The Grotesque by Philip Thomson, Grotesque The World Wide Web Site

Showing posts with label Ancient. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Ancient. Show all posts

Friday, April 10, 2009

Grotesque Aesthetics

Monday, February 9, 2009

Vandalized Art

Again from T. Siebers article:

"What is the impact of damage on classic works of art from the past? It is true that we strive to preserve and repair them, but perhaps the accidents of history have the effect of renewing rather than destroying art works. Vandalized works seem strangely modern. In 1977 a vandal attacked a Rembrandt self-portrait with sulfuric acid, transforming the masterpiece forever and regrettably."

Would vandalized works become more emblematic of the aesthetic, if we did not restore them, as the Venus de Milo has not been restored?

Vandalism modernizes art works, for better or worse, by inserting them in an aesthetic tradition increasingly preoccupied with disability. Only the historical unveiling of disability accounts for the aesthetic effect of vandalized works of art. Damaged art and broken beauty are no longer interpreted as ugly... They also suggest that experimentation with aesthetic form reflects a desire to experiment with human form. Beholders discover in vandalized works an image of disability that asks to be contemplated not as a symbol of human imperfection but as an experience of the corporeal variation found everywhere in modern life."

While much have been written about vandalized works of art here and here are some very basic articles for well known works of art like "Guernica" and Michelangelo's "Pietà" or Duchamp's "Fountain".

Felix Gmelin, a Swedish artist, in his exhibition "Art Vandals" has been interested in artworks that have literally been destroyed in museums, galleries, or other public spaces. In "Art Vandals", Felix Gmelin reinterprets twelve works that have been subjected to vandalism.

'Repeatedly, the attacks occure, often committed by people who describes themselves as artists. Museums are reluctant to release information about these events, fearing that they will inspire future outrages. Or are there other reasons?'

A webbproject Art Vandales has been made and into Felix Gmelin's official web site two relevant essays (Daniel Birnbaum's "The Art of Destruction" and Dario Gamboni's "Recreating Destroyed Destructions: Felix Gmelin's Art Vandals") cast more light on the subject.

Felix Gmelin's "Kill Lies All After Pablo Picasso (1937) & Tony Shafrazi (1974)" artwork belongs to Saatchi Galery and is a reproduction of a section of Pablo Picasso's celebrated 1937 anti-war masterpiece Guernica following its defacement by young art student (and now art dealer) Tony Shafrazi while on loan to The Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1974. Gmelin's painting takes its title from the words daubed by Shafrazi in red spray paint across the work's surface; an attempt, he claimed afterwards, "to bring the art absolutely up to date, to retrieve it from history and give it life." The painting belongs to an ongoing series in which the artist meticulously replicates well-known paintings and sculptures as they appeared in the immediate aftermath of similar acts of vandalism or disfigurement.

Gert Jan Kocken's exhibition "Defacing" at the Artefact Festival 2009,"...is a series of photographs of religious objects that were destroyed during the Reformation and the Beeldenstorm (Image War) which raged across Europe in several waves in the 16th century. Gert Jan Kocken discovered that very few artworks with visible damage survived. The damaged artifacts which have survived on the spot (reliefs and paintings) and scratched out missal texts, have rarely if ever systematically been illustrated. The sharpness of Kocken's prints and their format give them a material quality that closely approaches that of the original sculptures and paintings, and makes them even better and more easily visible than in their location in churches, or in museum depots. In the exhibition the emphasis comes to lie on the faces of the saints, chiselled away or scratched out in a way that is as malicious as it is meticulous, while the rest of the image remains almost entirely intact.

Gert Jan Kocken places history and memory in relation to the image. Defacing is a series of photographs that focus attention on the fury that images have provoked in the past. In doing so, he poses questions about the way the image exercises its power today."

Auguste Rodin, The Thinker, collection Singer Museum, Laren Defacement: 17 January 2007

Thomas Beckett, St. Andrew, North Burlingham Defacement: 1538

Anna retable, Domkerk, Utrecht, the Netherlands Defacement: 7 March 1580

Annunciation, Swanden. Defacement 21 december 1528

Willem V, Assen. Defacement 1795

In "The Past in the Present" photography series Gert Jan Kocken also looks at moments of important historical change. Among other images, we see paintings made by Adolf Hitler at his 18th year of age when he submitted his watercolours as application for the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and he was not admitted.

From "The Art of Iconoclasm" by Sven Lütticken

Gert Jan Kocken "...began his Disaster Sites series in 1999: using a view camera, he photographed various locations where a great disaster had once occurred, printing the photographs in large format to produce a monumental, detailed image. Because the photographs were made long after the disaster involved, there is nothing more to be seen than a landscape, and there is only the memory of what took place at this specific location. For instance, the majestic views of the slope of Mont Blanc, with the entrance to the tunnel of the same name, or the sea at Zeebrugge, or the park-like space in the midst of the Bijlmer receive a certain charge – a tension between the aesthetic image and what collective memory knows about the place. A similar series was to be seen in the group show ‘Something Happened’, which Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam (SMBA) assembled with work by Kocken for the Amsterdam Art Fair in 2004, this time with life-sized photographs of places in Amsterdam where a murder, suicide or a shocking disclosure had taken place. At first glance all are ordinary locations – with, however, a charged history."

"The history of iconoclasm is very closely interwoven with theological and philosophical ideas that may differ by time and place, but which are often quite profoundly rational. It began with the iconoclastic controversy in the Byzantine Empire, which ran on nearly a century after 726, the year that the Emperor Leo III had a mosaic of Christ that was above the entrance to his palace removed in favour of a simple cross. This interweaving of iconoclasm and religion continued through modern, abstract art by Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian and others. [1] Iconoclasm took on a symbolic, aesthetic form in the work of these artists. Over the centuries most forms of iconoclasm have however gone down in history as instances and examples of the act of destruction, and not so mush the specific remains of the deed. In other words, iconoclasm is mostly understood to be just blind vandalism, and has therefore become a taboo in the modern context of far-reaching musealisation and conservation of art and a constantly expanding system of historical preservation."

For a more comprehensive examination of modern iconoclasm, The destruction of art: iconoclasm and vandalism since the French Revolution by Dario Gamboni looks at deliberate attacks against works of art in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

"We shall not have demolish everything unless we demolish even the ruins! Now I can not think of another way than making beautiful, well arranged buildings out of them"

Alfred Jarry "Ubu Enchained"

Marcel Duchamp's readymade "L.H.O.O.Q" ("Elle a chaud au cul" literally translates into "She has heat in the ass" but Duchamp gave a loose translation of "L.H.O.O.Q." as "there is fire down below" - in fact the term avoir chaud au cul is slang used in the sense of "to be horny".) is the objet trouvé (found object) - a cheap postcard reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa - onto which Duchamp drew a mustache and beard in pencil and appended the title.

Marcel Duchamp's "L.H.O.O.Q." also poses questions about the way the image exercises its power today and if a vandalized cheap reproduction of Mona Lisa is justified or acclaimed as a great work of art, then the vandalized cheap reproductions of icons of "Virgin Mary and Holy Child Jesus" on January 2007, at the School of Theology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece, they can also claim their justification as great works of art.

"My point is not to encourage vandalism but to use it to query the effect that disability has on aesthetic appreciation." again from T. Siebers's article. But as vandalism very often poses aesthetic and political questions over its damaged objects, the questions coming from the vandalized image of Virgin Mary are: Does the veil symbolize a burga, a chador, a niqab and therefore a holy Christian turned into a devout Muslim, or more plainly a holy Christian turned into a musketeer infantry soldier of social change?

A rather conservative view on art vandalism, can be found in "Why art vandals strike" Katrina Kuntz's article with a list of ten exceptional examples of vandalized art between 1972 and 1998.

"What is the impact of damage on classic works of art from the past? It is true that we strive to preserve and repair them, but perhaps the accidents of history have the effect of renewing rather than destroying art works. Vandalized works seem strangely modern. In 1977 a vandal attacked a Rembrandt self-portrait with sulfuric acid, transforming the masterpiece forever and regrettably."

Would vandalized works become more emblematic of the aesthetic, if we did not restore them, as the Venus de Milo has not been restored?

Vandalism modernizes art works, for better or worse, by inserting them in an aesthetic tradition increasingly preoccupied with disability. Only the historical unveiling of disability accounts for the aesthetic effect of vandalized works of art. Damaged art and broken beauty are no longer interpreted as ugly... They also suggest that experimentation with aesthetic form reflects a desire to experiment with human form. Beholders discover in vandalized works an image of disability that asks to be contemplated not as a symbol of human imperfection but as an experience of the corporeal variation found everywhere in modern life."

While much have been written about vandalized works of art here and here are some very basic articles for well known works of art like "Guernica" and Michelangelo's "Pietà" or Duchamp's "Fountain".

Felix Gmelin, a Swedish artist, in his exhibition "Art Vandals" has been interested in artworks that have literally been destroyed in museums, galleries, or other public spaces. In "Art Vandals", Felix Gmelin reinterprets twelve works that have been subjected to vandalism.

'Repeatedly, the attacks occure, often committed by people who describes themselves as artists. Museums are reluctant to release information about these events, fearing that they will inspire future outrages. Or are there other reasons?'

A webbproject Art Vandales has been made and into Felix Gmelin's official web site two relevant essays (Daniel Birnbaum's "The Art of Destruction" and Dario Gamboni's "Recreating Destroyed Destructions: Felix Gmelin's Art Vandals") cast more light on the subject.

Felix Gmelin's "Kill Lies All After Pablo Picasso (1937) & Tony Shafrazi (1974)" artwork belongs to Saatchi Galery and is a reproduction of a section of Pablo Picasso's celebrated 1937 anti-war masterpiece Guernica following its defacement by young art student (and now art dealer) Tony Shafrazi while on loan to The Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1974. Gmelin's painting takes its title from the words daubed by Shafrazi in red spray paint across the work's surface; an attempt, he claimed afterwards, "to bring the art absolutely up to date, to retrieve it from history and give it life." The painting belongs to an ongoing series in which the artist meticulously replicates well-known paintings and sculptures as they appeared in the immediate aftermath of similar acts of vandalism or disfigurement.

Gert Jan Kocken's exhibition "Defacing" at the Artefact Festival 2009,"...is a series of photographs of religious objects that were destroyed during the Reformation and the Beeldenstorm (Image War) which raged across Europe in several waves in the 16th century. Gert Jan Kocken discovered that very few artworks with visible damage survived. The damaged artifacts which have survived on the spot (reliefs and paintings) and scratched out missal texts, have rarely if ever systematically been illustrated. The sharpness of Kocken's prints and their format give them a material quality that closely approaches that of the original sculptures and paintings, and makes them even better and more easily visible than in their location in churches, or in museum depots. In the exhibition the emphasis comes to lie on the faces of the saints, chiselled away or scratched out in a way that is as malicious as it is meticulous, while the rest of the image remains almost entirely intact.

Gert Jan Kocken places history and memory in relation to the image. Defacing is a series of photographs that focus attention on the fury that images have provoked in the past. In doing so, he poses questions about the way the image exercises its power today."

Auguste Rodin, The Thinker, collection Singer Museum, Laren Defacement: 17 January 2007

Thomas Beckett, St. Andrew, North Burlingham Defacement: 1538

Anna retable, Domkerk, Utrecht, the Netherlands Defacement: 7 March 1580

Annunciation, Swanden. Defacement 21 december 1528

Willem V, Assen. Defacement 1795

In "The Past in the Present" photography series Gert Jan Kocken also looks at moments of important historical change. Among other images, we see paintings made by Adolf Hitler at his 18th year of age when he submitted his watercolours as application for the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and he was not admitted.

From "The Art of Iconoclasm" by Sven Lütticken

Gert Jan Kocken "...began his Disaster Sites series in 1999: using a view camera, he photographed various locations where a great disaster had once occurred, printing the photographs in large format to produce a monumental, detailed image. Because the photographs were made long after the disaster involved, there is nothing more to be seen than a landscape, and there is only the memory of what took place at this specific location. For instance, the majestic views of the slope of Mont Blanc, with the entrance to the tunnel of the same name, or the sea at Zeebrugge, or the park-like space in the midst of the Bijlmer receive a certain charge – a tension between the aesthetic image and what collective memory knows about the place. A similar series was to be seen in the group show ‘Something Happened’, which Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam (SMBA) assembled with work by Kocken for the Amsterdam Art Fair in 2004, this time with life-sized photographs of places in Amsterdam where a murder, suicide or a shocking disclosure had taken place. At first glance all are ordinary locations – with, however, a charged history."

"The history of iconoclasm is very closely interwoven with theological and philosophical ideas that may differ by time and place, but which are often quite profoundly rational. It began with the iconoclastic controversy in the Byzantine Empire, which ran on nearly a century after 726, the year that the Emperor Leo III had a mosaic of Christ that was above the entrance to his palace removed in favour of a simple cross. This interweaving of iconoclasm and religion continued through modern, abstract art by Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian and others. [1] Iconoclasm took on a symbolic, aesthetic form in the work of these artists. Over the centuries most forms of iconoclasm have however gone down in history as instances and examples of the act of destruction, and not so mush the specific remains of the deed. In other words, iconoclasm is mostly understood to be just blind vandalism, and has therefore become a taboo in the modern context of far-reaching musealisation and conservation of art and a constantly expanding system of historical preservation."

For a more comprehensive examination of modern iconoclasm, The destruction of art: iconoclasm and vandalism since the French Revolution by Dario Gamboni looks at deliberate attacks against works of art in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

"We shall not have demolish everything unless we demolish even the ruins! Now I can not think of another way than making beautiful, well arranged buildings out of them"

Alfred Jarry "Ubu Enchained"

Marcel Duchamp's readymade "L.H.O.O.Q" ("Elle a chaud au cul" literally translates into "She has heat in the ass" but Duchamp gave a loose translation of "L.H.O.O.Q." as "there is fire down below" - in fact the term avoir chaud au cul is slang used in the sense of "to be horny".) is the objet trouvé (found object) - a cheap postcard reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa - onto which Duchamp drew a mustache and beard in pencil and appended the title.

Marcel Duchamp's "L.H.O.O.Q." also poses questions about the way the image exercises its power today and if a vandalized cheap reproduction of Mona Lisa is justified or acclaimed as a great work of art, then the vandalized cheap reproductions of icons of "Virgin Mary and Holy Child Jesus" on January 2007, at the School of Theology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece, they can also claim their justification as great works of art.

"My point is not to encourage vandalism but to use it to query the effect that disability has on aesthetic appreciation." again from T. Siebers's article. But as vandalism very often poses aesthetic and political questions over its damaged objects, the questions coming from the vandalized image of Virgin Mary are: Does the veil symbolize a burga, a chador, a niqab and therefore a holy Christian turned into a devout Muslim, or more plainly a holy Christian turned into a musketeer infantry soldier of social change?

A rather conservative view on art vandalism, can be found in "Why art vandals strike" Katrina Kuntz's article with a list of ten exceptional examples of vandalized art between 1972 and 1998.

Friday, January 30, 2009

"Damaged'' Ancient Greek Statues

Most of ancient Greek statues have been considered as representations of the ideal aesthetic beauty but many of them are eternally "damaged", like Nike of Samothrace

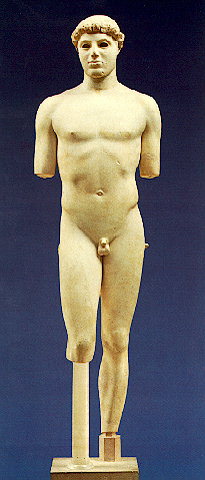

or Kritios Boy from Acropolis

and Kouros of Paros

and Demeter of Cnidus

and karyatides

and Hermes of Praxiteles

and many more...

or Kritios Boy from Acropolis

and Kouros of Paros

and Demeter of Cnidus

and karyatides

and Hermes of Praxiteles

and many more...

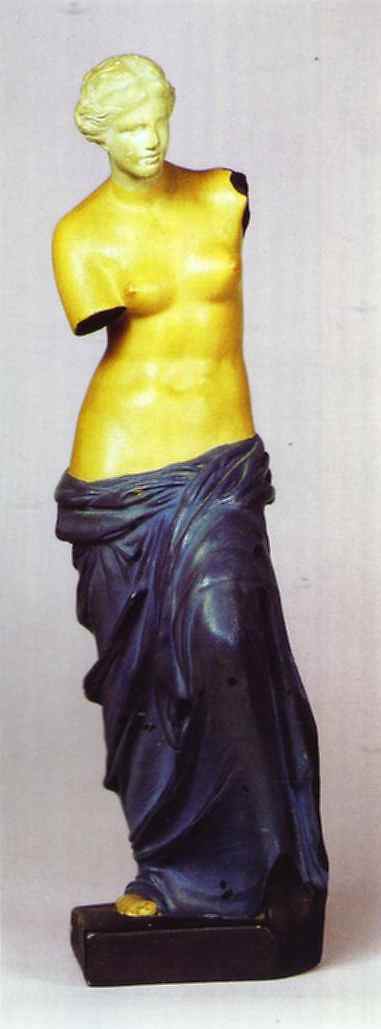

Venus de Milo

"It is often the presence of disability that allows the beauty of an art work to endure over time. Would the Venus de Milo still be considered one of the great examples of both aesthetic and human beauty if she still had both her arms?"

from T. Siebers's article again on "Disability Aesthetics",

and he continues:

"Perhaps it is an exaggeration to consider the Venus disabled, but René Magritte did not think so. He painted his version of the Venus, "Les Menottes de cuivre", in flesh tones and colorful drapery but splashed blood-red pigment on her famous arm-stumps, giving the impression of a recent and painful amputation"

we come across the many damaged ancient Greek sculptures

from T. Siebers's article again on "Disability Aesthetics",

and he continues:

"Perhaps it is an exaggeration to consider the Venus disabled, but René Magritte did not think so. He painted his version of the Venus, "Les Menottes de cuivre", in flesh tones and colorful drapery but splashed blood-red pigment on her famous arm-stumps, giving the impression of a recent and painful amputation"

we come across the many damaged ancient Greek sculptures

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)