"Most noble and illustrious drinkers, and you thrice precious

pockified blades (for to you, and none else, do I dedicate my

writings), Alcibiades, in that dialogue of Plato's, which is

entitled The Banquet, whilst he was setting forth the praises of

his schoolmaster Socrates (without all question the prince of

philosophers), amongst other discourses to that purpose, said that

he resembled the Silenes. Silenes of old were little boxes, like

those we now may see in the shops of apothecaries, painted on the

outside with wanton toyish figures, as harpies, satyrs, bridled

geese, horned hares, saddled ducks, flying goats, thiller harts,

and other such-like counterfeited pictures at discretion, to excite

people unto laughter, as Silenus himself, who was the foster-father

of good Bacchus, was wont to do; but within those capricious

caskets were carefully preserved and kept many rich jewels and fine

drugs, such as balm, ambergris, amomon, musk, civet, with several

kinds of precious stones, and other things of great price. Just

such another thing was Socrates. For to have eyed his outside, and

esteemed of him by his exterior appearance, you would not have

given the peel of an onion for him, so deformed he was in body, and

ridiculous in his gesture. He had a sharp pointed nose, with the

look of a bull, and countenance of a fool: he was in his carriage

simple, boorish in his apparel, in fortune poor, unhappy in his

wives, unfit for all offices in the commonwealth, always laughing,

tippling, and merrily carousing to everyone, with continual gibes

and jeers, the better by those means to conceal his divine

knowledge. Now, opening this box you would have found within it a

heavenly and inestimable drug, a more than human understanding, an

admirable virtue, matchless learning, invincible courage,

unimitable sobriety, certain contentment of mind, perfect

assurance, and an incredible misregard of all that for which men

commonly do so much watch, run, sail, fight, travel, toil and

turmoil themselves."

But grotesque world is not abound of political correct attributes; it's rather the opposite. That's what we come across in Chapter 1.LII.—'How Gargantua caused to be built for the Monk the Abbey of Theleme' when Gargantua and the Monk are setting up the special rules under which the Abbey of Theleme will be organised:

"Item, Because at that time they put no women into nunneries but

such as were either purblind, blinkards, lame, crooked,

ill-favoured, misshapen, fools, senseless, spoiled, or corrupt; nor

encloistered any men but those that were either sickly, subject to

defluxions, ill-bred louts, simple sots, or peevish trouble-houses.

But to the purpose, said the monk. A woman that is neither fair nor

good, to what use serves she? To make a nun of, said Gargantua.

Yea, said the monk, and to make shirts and smocks. Therefore was it

ordained that into this religious order should be admitted no women

that were not fair, well-featured, and of a sweet disposition; nor

men that were not comely, personable, and well conditioned."

So, when the Abbey of Theleme has been built, 'The inscription set upon the great gate of Theleme' in Chapter 1.LIV is writing:

"...Here enter not base pinching usurers, Pelf-lickers, everlasting

gatherers, Gold-graspers, coin-gripers, gulpers of mists, Niggish

deformed sots, who, though your chests Vast sums of money should to

you afford, Would ne'ertheless add more unto that hoard, And yet

not be content,—you clunchfist dastards, Insatiable fiends, and

Pluto's bastards, Greedy devourers, chichy sneakbill rogues,

Hell-mastiffs gnaw your bones, you ravenous dogs.

You beastly-looking fellows,

Reason doth plainly tell us

That we should not

To you allot

Room here, but at the gallows,

You beastly-looking fellows...

...Grace, honour, praise, delight,

Here sojourn day and night.

Sound bodies lined

With a good mind,

Do here pursue with might

Grace, honour, praise, delight...

...Blades of heroic breasts

Shall taste here of the feasts,

Both privily

And civilly

Of the celestial guests,

Blades of heroic breasts...

...Here enter you all ladies of high birth, Delicious, stately,

charming, full of mirth, Ingenious, lovely, miniard, proper, fair,

Magnetic, graceful, splendid, pleasant, rare, Obliging, sprightly,

virtuous, young, solacious, Kind, neat, quick, feat, bright, compt,

ripe, choice, dear, precious. Alluring, courtly, comely, fine,

complete, Wise, personable, ravishing, and sweet, Come joys enjoy.

The Lord celestial Hath given enough wherewith to please us

all."

In the Second Book, Chapter 2.I.—'Of the original and antiquity of the great

Pantagruel', when Rabelais describes what it was the world before the birth of giants, strange accidents occured:

"However, account you it for a truth that everybody then did most

heartily eat of these medlars, for they were fair to the eye and in

taste delicious. But even as Noah, that holy man, to whom we are so

much beholding, bound, and obliged, for that he planted to us the

vine, from whence we have that nectarian, delicious, precious,

heavenly, joyful, and deific liquor which they call the piot or

tiplage, was deceived in the drinking of it, for he was ignorant of

the great virtue and power thereof; so likewise the men and women

of that time did delight much in the eating of that fair great

fruit, but divers and very different accidents did ensue thereupon;

for there fell upon them all in their bodies a most terrible

swelling, but not upon all in the same place, for some were swollen

in the belly, and their belly strouted out big like a great tun, of

whom it is written, Ventrem omnipotentem, who were all very honest

men, and merry blades. And of this race came St. Fatgulch and

Shrove Tuesday (Pansart, Mardigras.). Others did swell at the

shoulders, who in that place were so crump and knobby that they

were therefore called Montifers, which is as much to say as

Hill-carriers, of whom you see some yet in the world, of divers

sexes and degrees. Of this race came Aesop, some of whose excellent

words and deeds you have in writing. Some other puffs did swell in

length by the member which they call the labourer of nature, in

such sort that it grew marvellous long, fat, great, lusty,

stirring, and crest-risen, in the antique fashion, so that they

made use of it as of a girdle, winding it five or six times about

their waist: but if it happened the foresaid member to be in good

case, spooming with a full sail bunt fair before the wind, then to

have seen those strouting champions, you would have taken them for

men that had their lances settled on their rest to run at the ring

or tilting whintam (quintain). Of these, believe me, the race is

utterly lost and quite extinct, as the women say; for they do

lament continually that there are none extant now of those great,

&c. You know the rest of the song. Others did grow in matter of

ballocks so enormously that three of them would well fill a sack

able to contain five quarters of wheat. From them are descended the

ballocks of Lorraine, which never dwell in codpieces, but fall down

to the bottom of the breeches. Others grew in the legs, and to see

them you would have said they had been cranes, or the

reddish-long-billed-storklike-scrank-legged sea-fowls called

flamans, or else men walking upon stilts or scatches. The little

grammar-school boys, known by the name of Grimos, called those

leg-grown slangams Jambus, in allusion to the French

word jambe,

which signifieth a leg. In others, their nose did grow so, that it

seemed to be the beak of a limbeck, in every part thereof most

variously diapered with the twinkling sparkles of crimson blisters

budding forth, and purpled with pimples all enamelled with thickset

wheals of a sanguine colour, bordered with gules; and such have you

seen the Canon or Prebend Panzoult, and Woodenfoot, the physician

of Angiers. Of which race there were few that looked the ptisane,

but all of them were perfect lovers of the pure Septembral juice.

Naso and Ovid had their extraction from thence, and all those of

whom it is written, Ne reminiscaris. Others grew in ears, which

they had so big that out of one would have been stuff enough got to

make a doublet, a pair of breeches, and a jacket, whilst with the

other they might have covered themselves as with a Spanish cloak:

and they say that in Bourbonnois this race remaineth yet. Others

grew in length of body, and of those came the Giants, and of them

Pantagruel."

What it might be also relevant to disablity aesthetics and it deserves to be mentioned here is in Chapter 2.XIX.—'How Panurge put to a nonplus the Englishman that

argued by signs', in which, Panurge and an Englishman named Thaumast, communicate and discuss philosophical problems "...by signs only without speaking, for the matters are so

abstruse, hard, and arduous, that words proceeding from the mouth

of man will never be sufficient for unfolding of them to my(their) liking."

The argument will be done through signs created with movements of the members of their body, reminding us the Sign Language or Gesture Language, that is used by deaf and not deaf people for communicating each other.

In such a subversive book, to keep on searching on what it might be political correct to our contemporary view, regarding disability, someone, will loose the most of what that book has to offer.

What if in Chapter 2.XXVII.—'How Pantagruel set up one trophy in memorial

of their valour, and Panurge another in remembrance of the hares.

How Pantagruel likewise with his farts begat little men, and with

his fisgs little women; and how Panurge broke a great staff over

two glasses', little man and women is treated like a birth of Pantagruel's farts:

"...but with the fart that he let the earth trembled nine

leagues about, wherewith and with the corrupted air he begot above

three and fifty thousand little men, ill-favoured dwarfs, and with

one fisg that he let he made as many little women, crouching down,

as you shall see in divers places, which never grow but like cow's

tails, downwards, or, like the Limosin radishes, round. How now!

said Panurge, are your farts so fertile and fruitful? By G—, here

be brave farted men and fisgued women; let them be married

together; they will beget fine hornets and dorflies. So did

Pantagruel, and called them pigmies. Those he sent to live in an

island thereby, where since that time they are increased mightily.

But the cranes make war with them continually, against which they

do most courageously defend themselves; for these little ends of

men and dandiprats (whom in Scotland they call whiphandles and

knots of a tar-barrel) are commonly very testy and choleric; the

physical reason whereof is, because their heart is near their

spleen."

Disability aesthetics should be concerned on the political correctness of its own expression? Disability aesthetics should feel comfortable whenever there is a self-mocking attitude towards its own beliefs? I believe yes, for many reasons.

[..................cont.]

What to my thought is extremely important and powerfull in this book, is its debasing and uncrowning manner to what it is commonly accepted as 'hight', the "...negation of the entire order of life (including the prevailing truth), a negation closely linked to the affirmation of that which is born anew" (M. Bakhtin).

What affiliate disability aesthetics with 'Gargantua and Pantagruel' and what makes this book looking so contemporary to our view, is the notion that the role of art is to make bourgeoisie feel uncomfortable; and this critical function is specifically characteristic to the arts since 'the crisis of the art", as Lyotard put it, locating it in the past century.

'Rabelais and His World' is the title of Michail Bakhtin's famous book dedicated to Rabelais's 'Gargantua and Pantagruel' novel. Bakhtin's book offered a refreshening and revealing, althought controversial to his contemporaries, view on many underestimated and misunderstanded aspects of the 'Rebelaisian' cosmos and through his 'grotesque realism' and 'carnivalesque' theories he studied the interaction between the social and the literary, as well as the meaning of the body.

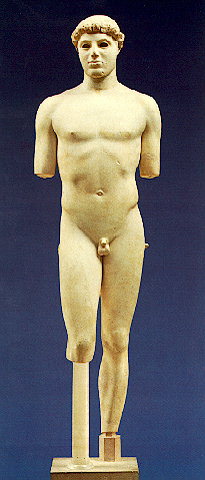

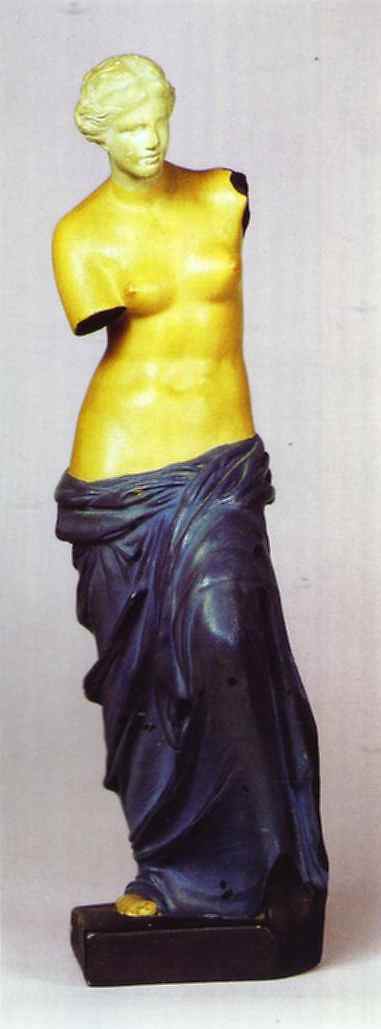

In his fifth chapter of his book named 'the Grotesque image of the body and Its Sources' Bakhtin describes as 'exaggeration, hyperbolism, excessiveness' the 'generally consider fundamental attributes of the grotesque style.'

According to Bakhtin the grotesque world is that of great ambivalence; in one image of whom it is combined both the positive and the negative poles.

Here are some excerpts of the 5th chapter:

+in+Trafalgar+Square.jpg)